by Mary Jo Watts (mid0nz)

Arwel Wyn Jones is a beloved figure in the Sherlock fandom. It all started with a tweet, a photo of an empty studio, the blank canvas of series three. Each day he would post something new. A scaffold. A wall. Some crew members joking around. “What’s this?” he’d ask about a board with some holes in it, and the guesses would come tumbling in by the hundreds before he would tweet its more famous side, confirmation in the form of that famous bullet riddled smiley face. Over the course of the next several weeks Arwel showed us in detail what we’d all taken for granted, the amazing work of scores of people who design and construct the cozy wreck of a place, that fictional affordable Baker Street flat where our cherished consulting detective deduces, pouts and preens.

Sherlock may be on hiatus as usual, but the fandom has a new flat to make our home. Earlier this month, in “The Abominable Bride” we were treated to Arwel’s Victorian version of his modern version of the Victorian 221b. Delightful!

I’m creating my version of his modern 221b in my home office. I’ve hunted down all the iconic props and dressings. I’ve even managed to import from the UK a roll of The Wallpaper. I’ve spent countless days scouring screen caps of Sherlock so I could catalog all the dressings including every single book. Arwel designed the most vivid set of rooms in my mind palace. I’m obsessive about his sets, yes. In this I am not alone. (Wallpaperlock is one of my favorite fandom creations.)

Preproduction on series four starts soon, and with it more teasers and tweets. Arwel graciously made time to talk with me before the madness begins. I should I say before he begins the madness!

-MJW

Mary Jo Watts: I want to start at the beginning and ask you about conceptualizing the version of 221b Baker Street set we see in the unaired pilot of Sherlock and how it evolved into the 221b we see in The Great Game, the first episode you filmed in series one. What was the process?

Arwel Wyn Jones: Well, it was strange for me, because I co-designed the pilot with Edward Thomas, who I’d worked with on Doctor Who a lot, and I was finishing off the current series of Torchwood at the time as a stand-by art director. So they’d already started the process of designing the actual framework, the flattage as it were, of 221b, and they’d gone down the road of the backstory to it, that there was a restaurant downstairs, and there had been a kitchen on the upper floor and stuff like this. So by the time I got on board, and I was more involved in dressing the set and the painting and all that kind of thing. When I was doing that, the ethos of that pilot was that it was very much a Sherlock Holmes story, a version of Sherlock Holmes, but based in the 20th century, with elements of the 20th century.

Then, because we were very lucky to have the luxury of a pilot, when the BBC wanted something different, we could look at it and go, “What worked? What didn’t work? What can we do?” All that stuff.

And there were numerous things I wasn’t all that happy about as far as the shape of the floor plan and stuff of the sets that I could tweak and play around with. But also the main thing was that ethos changed in that, when looking at the programme, everyone realised that it worked really well in the 21st century. So we flipped it on its head. It became a 21st century romp, action-adventure with elements of Sherlock Holmes in it. So that changed the way we looked at the whole thing, really.

For me, the flat became a bit of a transient space that had been rented out to numerous people over the years, not necessarily just been part of a restaurant for Mrs. Hudson. And that kind of gave me the leeway to layer in the different wallpapers, finishes, and all these different textures, because in my head I was starting in, say, the ‘50s, and every decade I was layering in something someone had left their mark in that space that they lived in.

MJW: Like the modern Danish furniture?

AWJ: Yeah, exactly. So there’s wallpapers from different decades right up to the modern age. The same with the furniture; you’ve got some Danish furniture from the ‘70s and ‘50’s, some Victorian stuff just thrown in there just for a little bit of authenticity, and some really modern stuff.

You know, there was just the things like the [Alessi] fruit bowl. When we did series one, that was very, very, very bang-on, current. Equally with the artwork, like the skull painting I got John Pinkerton to do. We played around with this idea. He was doing some skull paintings in the workshop, and I just asked him, could he split it into three images and put one on each piece of Perspex and layer them? What I wanted to do is space them apart so that as you move, the camera, it would have a slightly 3D look to it, but he stuck them all together, which still gives you something quite nice. So that was very, very bang-on period, you know, for what was it now, 2010?

MJW: Yes.

AWJ: I know I’m getting old. So yeah, that was the whole idea, really. To make it a far more transient space and to have fun with it, you know? No one would really live in a house decorated like that, but you need it to look good on camera. And because by that point [director] Paul McGuigan was involved in it, who’s very much into his wallpapers as well, and he’s great for pushing you to find your limits, because he’ll tell you if he doesn’t like something, but he’ll never tell you what he does like. You know, what to do. He’ll tell you once if you get it right, but it’s up to you to find that.

MJW: So working with Paul on “The Great Game”, what did you change or tweak?

AWJ: It was just finding the right kind of things. I didn’t necessarily change anything. It was just, “What do you think of this?” One of my anecdotes is, the wallpaper that everyone recognises now, is that the designer of Doctor Who walked through the studio whilst my decorator was putting it up and just shook his head and went, “I hope he knows what he’s doing.” And even McGuigan himself went, “Are you sure about this?”

MJW: After McGuigan directed Lucky Number Slevin with all of that wallpaper on François Séguin‘s sets? [laughing]

AWJ: Yeah, yeah. So it kind of put you in a situation where you’re going, “All right, am I sure about this? Not really.” But then, you got to take a bit of gambles, right?

MJW: So you’ve got this…I know way too much about the set, like I’ve catalogued everything on it. So you have the Zoffany wallpaper, the really famous wallpaper, and then on the side walls, it’s green. Was that painted wallpaper?

AWJ: Yeah, it’s Folded Paper, Anaglypta.

MJW: Ok. And then the other is vintage, the red and gold?

AWJ: Yeah. I’ve run out of it now.

MJW: Ah?

AWJ: Don’t know what I’m going to do. When we did the first series, there was like 20 rolls of it, so it was easy. It was one wall. There was loads. No one really expected Sherlock to go on this long.

MJW: So there’s got to be something in the series four plot that explains why the wallpaper’s changed, then.

AWJ: Well, we’ll see when I start. The walls were taken apart very, very carefully last time because I’m aware of this, but we’ll see how they come out of storage.

MJW: So can I ask you about some of the details of the sets? The things that I can’t figure out?

AWJ: Yeah.

MJW: So the portraits on the wall?

AWJ: Yeah. John Whalley did the pencil sketches.

MJW: Yes. So the Whalley’s sketch sort of catty-cornered to John Pinkerton’s skull. Who is that? It’s a face?

AWJ: John Whalley had a portfolio, just a stack of human anatomy sketches, and I just used stuff. They’re more about the study of the human anatomy rather than artwork as far as Sherlock’s concerned, but you get away with it as being artwork as well.

MJW: Like the foot.

AWJ: Yeah, because you know you got to be careful with Sherlock, because he wouldn’t be as flippant as just to use that, put art up, and hence why the skull is there. So yeah, that’s why, really.

MJW: So the record albums on the set- what are they?

AWJ: They were nothing specific.

MJW: Just hired albums?

AWJ: Yeah, it’s just stuff. There’s Easter eggs in there that I’ve always layered in, but there’s also stuff just to fill the space. You need so much stuff on the 221b set to get that level of clutter.

MJW: Yeah, so there were some items from The Sarah Jane Adventures on the set, right?

AWJ: Maybe. Yeah.

MJW: The Lavinia Smith book? Sarah Jane’s auntie’s book, The Teleology of the Virus? And the West End Power mug.

AWJ: Possibly, but you see, when we were dressing the set originally, it was next door to the Tardis and next door, the other side, to Sarah Jane’s loft. So you had three studios. You had the Tardis, you had 221b, and you had Sarah Jane. And then you had one big prop store that was the BBC’s. Now technically we weren’t the BBC, so we weren’t supposed to use any of the stuff off their shelves, but we may have just had them, you know, the odd little bit here and there just to help out. And equally, I have told a few people over the years that the original pieces of music on the music stand have Gallifreyan text on them because they were from the Tardis, from the original Tardis when we came back with Chris [Eccleston in the series reboot]. It’s a piece of music that’s been scanned and printed, but there’s also Gallifreyan text in amongst it.

MJW: I love it!.

AWJ: Now, of course, it’s John and Mary’s waltz [from “The Sign of Three” on the set].

MJW: Oh, right! I read somewhere that there are books on the set that fans sent in- Goethe’s Faust for example.

AWJ: Yeah, there is that. That’s the only one that a fan has sent in. It was just because it was quite a special thing, to be honest. It was an original Faust- And in the Conan Doyle books, there’s a reference to Sherlock having read it in the original German.

MJW: I’ve seen pictures with Mark Gatiss holding Moriarty’s Police Law.

AWJ: Yeah, he brought that in.

MJW: You mentioned that maybe Benedict had requests for books? Were there any other books on the set that people requested?

AWJ: He requested one once on set, but you’ve got to be careful with books because you’ve got to clear them.

MJW: Oh?

AWJ: You know, because you can’t just use them. As much as it’s nice if they do request something, they can’t do it on the day. You have to then go, “Hm. Sorry Ben, but no. We can’t really do that for you.” So yeah, we’ve had a couple requests like that. If they request something in time, then by all means, you know. I always accommodate as much as possible.

MJW: I feel like I’ve lived on that set. So you started off with the idea of layering things and having sort of the ages in 221b. How did it change, or does it change, from season to season?

AWJ: I think this time [in series four] we may need to show a little bit more of a time jump, but then technically speaking, we’ve only just left and gone on the aeroplane and come back [in “The Abominable Bride”]. So there’s no helping that, and that’s always been the case in between the series, you know. The only one where we’ve had the big gap is after the jump [“The Reichenbach Fall”].

And 221b, even then, had been kept exactly as it was. Seems a little bit odd that it doesn’t change, but then really there hasn’t been time for it to have.

MJW: I didn’t even think of that. [laughs] Yeah, you’re right. In story, it doesn’t. I mean maybe the flowers wilted between series two and three.

AWJ: Well, yeah. We’ve done a bit of that, and we put a lot of dust in for that initial look when you come in, so you get dust in the air and everything and the opening of the curtains to show there’d have been a bit of time, but the actual dressing of what goes where…

MJW: Is pretty exact.

AWJ: Mm.

MJW: So I’m interested in what you have to, working with the camera- I’ve talked Steve Lawes a lot about the cinematography of Sherlock. What do you have to do working with a director of photography [DoP] or with the other people on the set? Who do you work most closely with? And what concerns do you have to be aware of?

AWJ: The DoP’s always high up there and Costume. Especially on this show, because you know I worked really closely with Steve on the first one and we get on really well, and when he came back and did Three it was cool. But equally, because he hasn’t always done them, I’ve worked with three other DoPs on the show by now. So part of my responsibility is to make sure that the style stays, and I know that they’ve all got individual styles, but then the overall style of the show has to stay the same as well. But we work closely, like with Steve, he has a very specific way of lighting, and he likes to bounce strong light in through windows. So we deliberately painted everything a shade darker than it needs to look on camera for him, and there are certain things we do that give it a certain type of light, like aged newspaper on the windows and stuff like that. Definitely all DoPs like a lot of practical lamps, so there’s practical sources. But then, most designers do as well. You like to have a bit of texture within your frame.

MJW: So how do you choose the practicals? Some of them on the set are designer designer lamps.

AWJ: Yeah.

MJW: How did you decide which ones?

AWJ: Because they look good.

MJW: [laughing] Do you start off with an idea and then go find the lamps that match?

AWJ: Yeah, part of what you do as a design process, you make mood boards of the kind of things you like. For the beginning of 221b, it was a very eclectic mood board because you had that kind of Danish style mood going on. The furniture is quite trendy now, really difficult to get, but at the time it wasn’t. And I had a mood board of different types of skulls and stuff. And I come across this article in a design magazine, which just had this, I think it was like a Roundhead or something that had been sprayed gloss black. And I thought, “Well, that’s cool,” which is where the bison head came from. So I elaborated on that, really. You just pick on little ideas, and you try and gather everything.

I’ve done things over the years like at the beginning of series three—it didn’t really come to anything in the end because we became too busy—but every time, when a new member of the art department started, because obviously I start first, I asked everyone to do one sheet of what excited them in design at the moment so that we could put up on the wall, and I would have this nice mix of what’s current and what’s cool and what’s not and stuff. So I might try that again this year because I’m really excited now about having gone back to Victorian [in the 2016 Sherlock special, “The Abominable Bride”]. What was great- really nice about it was, I got to go do a Victorian version of my set rather than do a Victorian 221b.

MJW: Oh, I loved the moon lamp equivalent!

AWJ: Yeah. Yeah. There’s loads in there. I just looked at the whole set and just tried to get a Victorian equivalent of as much as possible, from their chairs to the sofa to the lamps to the pictures, the skull, all the kind of bits, really.

MJW: Is there anything in the 221b Victorian that you’re particularly fond of? Or that gave you a bit of a challenge to come up with?

AWJ: All of it’s a challenge, but it was a nice challenge because, like I say, rather than trying to reinvent the wheel as far as Sherlock’s 221b, which has been done as a Victorian set so many times, I got to do my version as a Victorian one, which was slightly different. And it’s that hyper-real thing about Sherlock anyway. Yes, you have to be relatively historically correct, but you can have fun as well. So, you know, there’re little nods- in the whole show there, really, a lot of little nods to the fans, but there was quite a few in 221b. The brass horn in the ear of the deer’s head was something I quite liked, the skull painting- the Vanity thing was really cool. So I love all that kind of Victorian obsession with death. I actually had three or four different [Victorian] options [for John Pinkerton’s skull]. I went with “All is Vanity”, in the end. I’ve actually used one of the other ones in Houdini and Doyle, which I’ve just finished recently.

MJW: Oh, did you?

AWJ: Yeah. [laughs]

MJW: Well, which one? Where is it? Can we look for it?

AWJ: You have to wait.

MJW: I have to wait. Ah. Rats.

You knew the Sherlock special was going to be a Victorian a couple years ago, right? This was an idea that was floating around for a while?

AWJ: No. No, they kept it to themselves.

MJW: Oh, did they?

AWJ: Yeah, I didn’t know until just before Christmas 2014. I started work on it in November, 2014. Lady Chatterley’s Lover we did just before that, and it was also for Hartswood [which produces Sherlock]. And it was whilst I was working on that that they told me. That’s why I had a lot of things already in my head by the time I started working on it.

MJW: What’s the first script you get? Is the read-through script? Or is there a pre-production script?

AWJ: Actually, that’s one of the last. It depends on whose script, but you get a pretty good idea of the layout of what happens. There will be a lot of dialogue changes, maybe, and sometimes the story pieces will change. But at least the locations very rarely change. They might add one or drop one by the end, but you go out and try and find locations and work out what you’re going to build the sets with, what you’re doing as part-builds on location maybe, but that’s one of the first things you do. When the script arrives I just look at it. It’s like a pile of problems, essentially. So then you just problem-solve. That’s what you do, but whilst you’re problem-solving, how would you achieve all these various elements, you’re adding design to it as well.

MJW: So tell me about Magnussen’s mind palace, because that thing is creepy and horrible and magnificent. How did you come about?

AWJ: It was trying to find the space for it. We looked at various different places. And again, it was down to schedule, because we had to do it in the last week whilst we were in the studio. We’d wrapped lots of other things. So we did it in the paint store of the studio. It’s where normally you go to paint everything up, so we cleared that out and just created the shelves and the labyrinth within an empty space. And by its nature, you just had to get all manner of stuff in there. And we just wanted weird stuff in there so that there was like little pointers of memory location.

MJW: Like crazy doll heads and bizarre things like that.

AWJ: Yeah. A rabbit holding a top hat. There’s loads in there. There was a little baby hippopotamus in a dog bed. There’s a load of things you didn’t see.

MJW: [laughs] I wish we could have seen them all. Because if we did, everybody would be looking at the significance of them. How much do you think about the significance or the symbolism of what you put on a set?

AWJ: It depends. If I’ve got time, a lot. If I don’t- I just want to make it look pretty. But one of my favourites that I saw, I think it was on Tumblr. In Kitty Riley’s’s flat [in “The Reichenbach Fall”], when Sherlock and John are sat beneath all the paintings and posters on the wall, we decorated that flat, but we put the lady that lived there’s paintings all back up, having cleared them, because I liked them, right? They looked nice. That was it.

MJW: So they were all part of the location.

AWJ: There were hers, from the location, yeah. And I saw this Tumblr account. They had backstory points for every single one of them.

MJW: That’s what we do. [laughing]

AWJ: Yeah. Yeah, nice. It would be lovely to have had that much time to work that out, but that’s not reality, you know. At the beginning of a series of three, I get seven weeks prep.

MJW: For the whole series?

AWJ: For the whole series, so that’s not a lot. And then once we start shooting, we shoot in four and a half weeks, and during that four and a half weeks we prep the next one, and then there’s normally a half-week, to a week in between them. So there is no time to be very thoughtful and pondering about things. You’ve got to react to things and get going.

MJW: So I’m assuming that you work regularly with rental houses.

AWJ: Yeah.

MJW: So where do you get your props? How does that come about? Does the BBC have things in store that you can work with? You work with the houses?

AWJ: That’s what I was saying. The BBC really have- Because it’s not an in-house BBC production, they’d have to charge us anyway. And then they don’t have a very good back-up prop store anyway. Casuality have a modern-day thing they did in South Wales. But that’s no good to us, really, so we buy a lot. We hire a lot. I’ve got a very, very good set decorator who goes to the prop houses and I go with her sometimes, so it depends on the location. Some locations you could do, and that then also dictates to which prop houses you go. There’s a prop house called Modern Props, which have a lot of the kind of high-end, really expensive, nice stuff, like the snaking sofa at Magnussen’s, [in “His Last Vow”] for example.

MJW: The white one?

AWJ: Yeah. I didn’t even take out the whole one, because it’s a segmental thing. I think the whole one brand new is about 40 to 60 grand if you buy it. Just for the one sofa. You know, it’s ridiculous. So they have one there. You hire it for a certain amount of money, per segment, per week. So we just had to make it work within that space. When I get the script I break it down per location. A percentage of my budget goes to each location. Then we have to try and stick to that then to how much we spend on dressing it and whatever we do on construction and painting and wallpapering as well.

MJW: God, how do you get any sleep?

AWJ: I don’t get a lot, actually. The first series I didn’t get much at all.

MJW: So you’ve got all this stuff going on with the prep and going so, so quickly. What do you think, in terms of your background, prepared you to work at this pace and to be so amazing at it?

AWJ: [laughing] Nothing prepared me to work at this pace. A lot of it I think was that I’d come off Doctor Who, which is a rolling giant of a thing, and you’ve got to be across everything and work it. So in a way, just naturally the jobs I had worked on that I did, and it kind of got me there, you know. I grew up on a farm in North Wales where my father’s favourite saying is, “Necessity is the mother of invention,” so you turn your hand to anything. Back into it, really, is, you do a bit of everything. You’ve just got to be able to multitask lot of things, sort things out. And like I say, it’s problem-solving, really.

MJW: How did you into doing production design?

AWJ: The wrong way, as most people will tell you. I’d always loved films, so just one day I decided, “Right. I want to get into making programmes of some sort or other,” and phoned around until I got a job as a runner on a S4C Welsh language thing in Wales. Did that for a couple of years. Because they were very small scale kind of things, you ended up doing a bit more. Even as a runner, I was helping the art department a lot on stuff, and I asked whether they would take me on as a trainee, and the designer had liked what I’d been doing with him as a runner and decided to have me as an assistant. So I was very young, just no training, no college qualifications, ended up being an assistant designer on these Welsh dramas for a few years. And I kind of just went from there, and every break I’ve had, I’ve just worked as hard as I could to get to that next stage, really.

MJW: So do you work from storyboards or how do you prepare? I saw at one point for the pilot there was a miniature, right?

AWJ: Oh, yeah. Quite often, you build a white card model. If you’re going to build a set, you build a white card model. Or you build a 3D model on a computer, and then you can see angles, and you can work out the camera angles and where it’s going to be working and stuff like that. You always start with the plan on a piece of paper or a computer, then you build a model, and then off the model you can see if things work or don’t. You can tweak it, have a plan, show it to the director, all that kind of thing. But once again, that takes time. So when you prep in a series, on something new, you do it a lot, but if you’re having to build something in the middle of a series, very rarely do they make it to the model stage. Quite often, it goes like a quick pencil sketch on the back of a fag packet, and the construction guys start making, you know?

MJW: [laughs]

AWJ: But that’s where I’ve been lucky on Sherlock, is that the producers have always been really, really, really trusting and just let me go ahead with my craziness rather than wanting to see elements of what I’m doing.

MJW: So what’s the role of the director now that the series is rolling? You’ve got 221b set up. How do you work out the other sets? Do you just go and build them, and then maybe the director comes in and give you feedback? How does it work?

AWJ: Yeah, you don’t build them all up front anyway. Like I said, it’s on the roll, anyway. For 221b, because it’s an established look, it’s kind of protected. Every new director wants to reinvent the wheel, always, because they always want to say they’re going to make it with this or that, but generally the feel of that stays the same, and then anything else that’s story-specific, you discuss with them as to what requirements it needs to tell the story.

MJW: So is that generally it’s down to specifics about camera angles, or is it a look and aesthetic, or all of that?

AWJ: Yeah, all of that. All of that. Things like, for example, John and Mary’s house, right? You know, John and Mary’s house cropped up at one point in every script of series three but didn’t actually make it in into the final edit until the last one [“His Last Vow”]. And we were looking at various exteriors, interiors, and everything. We knew by that point that we had to do that little Christmas online thing as well-

MJW: “Many Happy Returns”?

AWJ: Yeah. You know. So you also wanted to have him sat on his own on the sofa and also, I once again, mirrored 221b in that. Not a lot of people caught that. There was a crystal skull vodka bottle in the cupboard to John’s right, and there was a lamp throwing the same kind of shadow on his left. So all the shapes and the things were in the same place again.

MJW: Ah. So “Many Happy Returns” wasn’t an excerpt or part of series three; it was definitely its own thing?

AWJ: Yeah, yeah. It was pre-episode of series three, wasn’t it? But we filmed it at the same time as we were in John and Mary’s flat when we did that bit where they were coming together, before we found Sherlock in the drug den.

MJW: Ah, the drug den. That, you’ve got your initials on the wall in the drug den, right?

AWJ: My son’s.

MJW: Oh, really? Oh, ok. I thought they were yours.

AWJ: It’s my son’s that I put everywhere since he was born. It’s in Doctor Who in various places. You can see them somewhere in every show I’ve done.

MJW: That’s so cool. So what are some of the other Easter eggs that people might have missed?

AWJ: Oh, god. I don’t know. We could start with the obvious ones. Even though it’s a modern day thing, there’s the Persian slipper for Sherlock’s tobacco… There’s the Moroccan table. There’s the stiletto, or my Leatherman, through the mail [on the mantle]. The skull, obviously. You know, all those little bits that are throwbacks to the actual mentions in the books. And then, as we go on, you put little elements of various things, like I say, mirroring shapes and things in John’s from 221b. The same when we’re doing the Victorian one [“The Abominable Bride”]. All the elements of the modern one are there, but in Victorian fashion. And then once you realise that it’s his Victorian in his head, you kind of realise then why. Because it’s his place that’s in with Victoriana.

MJW: In his mind palace. So did you think of the 221b as part of his mind palace when you were working on it? Or was it just, “Oh, we’re going to work on 221b. We’re going to un-modernise our modern version”?

AWJ: It was making a Victorian version of my 221b, which was what was nice, but also what it gave you was, you couldn’t work too far, because you’d give it away, but because you knew it was in his mind palace, it meant you could get away with things a little bit more. We have an old saying in our department: “It’s not a fucking documentary.”

MJW: [laughing] Love it!

I saw people on Setlock who looked like they were very careful about making sure the books were in the right spot and everything.

AWJ: Well, they had to be because we were going from the actual set to the set on a street. So you were cutting from one to the other, which is the most horrible of direct continuities you can get.

MJW: I was going to say, it sounds like a nightmare.

AWJ: And also which meant you couldn’t double up a lot of things. You had to take real stuff from the set. So we filmed some bits on the set, some bits on the street, and then we had to go back to the set. And I think we did it on the street twice, in two different places, so there were four lots of continuity that the guys had to get bang-on.

MJW: Hoo! That’s pretty amazing. So you knew you were going to be outside with it. To take something from such a dark interior—I mean, [director of photography] Suzie Lavelle’s’s interiors are really dark in this episode—to outside, is there anything you had to deal with in terms of the design to accommodate that?

AWJ: No, that was more of a lighting issue, to be honest. By its nature, because it’s Victorian, the colours and everything are quite dark anyway, so it wasn’t so much of an issue for me, but then balancing the lighting for Suzie was more of an issue.

MJW: So what other sets are you fond of, that you look at most fondly? And the ones that are nightmares?

AWJ: Quite often, what you’ll find is, the ones that are nightmares are the ones you end up being fond of because they were nightmares, and you got through it, and it ended up looking good. I loved Magnussen’s suite [in “His Last Vow”] in the end that we did because that was a last minute. That was a proper, trying-to-get-us-out-of-jail because we couldn’t find a location that worked to do everything, and we wanted to do that rig where we could lower Benedict slowly to the floor after being shot. So we needed to get underneath it and stuff. I had this idea I’d seen. Because of Magnussen being this multi-billionaire kind of guy, we were looking at locations, and we got this amazing location in his house, but we’d been looking at various apartments for sale and stuff that were in the tens of millions. One was like 50-60 million in London. And so I’d seen a lot of these interiors, and I’d started to build an idea in my head of what I’d like to do for his bedroom. And we weren’t finding anything near that we could afford or get the time to get into, you know?

MJW: Right.

AWJ: So we just, in the end, we built it, and I think it kind of worked, considering the high-end level of finishes it should have had. You could’ve spent a fortune on that, but I think we got away with it quite well. And that was a very last minute wallpaper idea as well because I was painting the walls, and I was going, “What am I doing? I’ve left out the most important part.” And I was like, “Shit, shit, shit. I haven’t got time!” So I literally—it was the day before, I think—I just ran down to John Lewis and got something.

MJW: [laughing] Did you have to stop and go, “Wait a minute. It is all about the wallpaper”?

AWJ: It is all about the wallpaper, yeah. Sometimes you can’t see the wood for the trees, you know?

MJW: So you had a vintage wallpaper supplier, right? For 221b?

AWJ: Yeah.

MJW: Do you have any surprises or anything that you didn’t expect from the fans and their reaction to your work?

AWJ: I never expected it to take off as much, especially that now what’s become an iconic wallpaper, which was a gamble on my part. As I’ve often said to whatever I get into. That’s my greatest, most pleasing thing out of the whole thing, I suppose, is that it’s become part and parcel of the show.

MJW: Absolutely.

AWJ: And genuinely the feel of it all, I think, is part and parcel of the show now, you know? Hence we’re talking. And I do this sort of thing a lot, and the actors and the producers are very, very, very kind in their comments always. It’s part of that world that we’ve created.

MJW: Absolutely. So what’s it like to interact with the fans? Because I’m guessing that on set, you’re on location some, but isn’t most of your work in the studio?

AWJ: No, it’s mostly location, really.

MJW: Oh, is it?

AWJ: But you do a lot of location interiors, which fans don’t get to see, you know? So I think, on average, say, it’s a four to four and a half week shoot, there’ll be a week in London where you get the exteriors, just to give you the London part. I’ll be a week in the studio probably between everything. Depending on what we end up doing, I’ll see a bit of it. There’ll be between a week and two exterior, and then, depending which way it goes then, between a week and two in interior locations and a bit of other locations in South Wales, all around.

MJW: So you worked on Doctor Who. You worked on Sherlock, and you got this amazing career. If you could work on any show, past or present that you haven’t, what would it be?

AWJ: Star Wars.

MJW: Yeah. What would you do for it?

AWJ: Well, make it better, obviously.

MJW: [laughs] Any ideas? Anything in particular?

AWJ: Well, no. It would depend on the script, wouldn’t it? I’m not going to say that I’d go back and redesign something someone’s already done, but you know, you get a new story, and you get to play with it, then do some things maybe a bit differently. The other one obviously is a Bond movie.

MJW: Oh. Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

AWJ: Or a Marvel one, to be honest. I mean, things are expanding so much now because Marvel movies are great. I think some of the best design of recent times have been really- Quite often, the superhero movies get overlooked at the award ceremonies, and there’s an awful lot of really good work that happens in them, you know?

MJW: Yes. So is it the sci-fi particularly, the kind of ability to-

AWJ: Well, sci-fi, westerns were what I grew up with. It’s the usual staples in there, isn’t it? Spies, westerns, and sci-fi, you know? Any of those and I’ll be happy.

MJW: [laughs] So I always ask this question of everybody that I talk to because it’s so hard for women to break into film and television production. If you were to give advice to a young woman who was trying to come up and be a production designer, what would you say?

AWJ: You should see my art department. It’s very often, me and Dafydd Shurmer are, if not the only boys, there’s only one or two others.

MJW: Cool. So the art department’s unique in that respect.

AWJ: No, not so much anymore. What you find is, it’s the higher end. Your DoPs, directors, that kind of thing. There’s more female designers, I would say, that I’m aware of at my level—maybe not on feature films, but at my level—there’s an awful lot of female designers and art directors, and some graphics, and all the elements of buyers. Most buyers, decorators I know of are female. There are few that buck the trend, but you know, both ways. And this job I’ve just done now, I was in Canada for six weeks doing the last two episodes, and I was really surprised. There was an awful lot of cameras, electricians that were female. It was great. It was lovely to see, you know?

MJW: Huh! So then, let me amend that a little bit. What would you tell a young person who wanted to become a production designer?

AWJ: I’d say, go and get a proper job.

MJW: [laughing] It’s a tight industry, right?

AWJ: It’s very, very difficult. You have to be willing to sacrifice a lot and give up a lot of time and just work out. You know, make the most of any little break you get.

MJW: So how often are you working on a production during the year on average?

AWJ: I used to say that, as a freelancer, if you worked 10 months out of 12, you’ve done really well. Normally, more like eight. I’ve been very lucky in that I’ve worked more than that over the last few years. But equally then, it takes its toll, you know?

MJW: Yeah. Absolutely.

AWJ: I think it was the second BAFTA Cymru award I got, because I forgot to do it in the first one- I apologised to my son for never being there. That’s one of the things.

MJW: So you work mainly in Wales and then location?

AWJ: I was just lucky that the big jobs have come on my doorstep rather than you have to go to them, you know? This year, I’ve been away more than I’ve been home. I’ve been in Manchester since May, then Canada for six weeks, but that’s one of the first times I’ve ever had to do that. I did a job in Scarborough a few years back, but this is the first time I’ve been abroad.

MJW: So what of your other work would you like to point people to see, that you’re especially proud of that you would say, “Hey!”

AWJ: I love the bits that I did on Sarah Jane. There’s a copper spaceship in Sarah Jane that I’m quite proud of. Russell T. Davies told me that it was the best spaceship that they ever had at Upper Boat.

MJW: That’s pretty amazing.

AWJ: Considering they did about five series of Doctor Who there. That’s pretty good. And there was the stuff on Wizards vs Aliens nearly killed me because that was a kids’ show that we had no money for, and we had an awful lot of ambition on that. We had the two ends of the spectrum: we had the wizards’ cave, and the science spaceship. So that was cool, but also difficult. All of them are different, different little things. The stuff we’ve just done now, I’m looking forward for everyone to see. There’s some really, really nice bits in that. Yeah, cool. Lots.

MJW: So what about locations? How do you work with a location manager?

AWJ: Well, once we’ve broken down the script as to what you need, you then get them sent out, and they come back with pictures, and you go, “Right. That’s nice,” or “I’ll tweak this. Give them that.” Then you go and see them and you work out then what you can do there. Then you go with a director and see if actually what you want to do will work in that space, or what I need to do to that space to make it work.

MJW: So I’m looking at 221b Victorian. How many people have to be involved to make this thing, and what are their roles? What departments have to be involved to see Victorian 221b happen?

AWJ: Well, just the art department.

MJW: Just the art department?

AWJ: Yeah. But the art department encompasses a designer, an art director, a set decorator, a buyer, a graphics person, a draftsman, and an art department assistant, a stand-by art director, two stand-by props, a stand-by chippie. The construction department will be a construction manager, three chippies. A painting department, who’s a painting and plastering HoD and three painters. And then there’s the props department. You have a props master, a charge hand, two dressers, and a storeman. They all work for me.

MJW: How do you coordinate all those people?

AWJ: Well, that’s why my art director and I have white hair.

MJW: [laughs]

AWJ: Well, Daf never used to have grey hair, but they’re coming through now. [laughs]

MJW: [laughs] I’m just sitting here trying to imagine, given the schedule, because you shoot in 21 days, right?

AWJ: 21 days actual shooting. Yeah, something like that.

MJW: And much time do you have for pre-production, did you say?

AWJ: Seven weeks. Normally we get the studio six weeks out.

MJW: Ok. I’m still trying to wrap my head around how all these people come together. So when you decide on the vision of what it’s going to look like, does everybody sort of pitch in with ideas?

AWJ: Yeah, people do often, and then I tell them all to bog off.

MJW: [laughs]

AWJ: Everyone’s got an opinion, all right? Always. It’s one of those things, and you get it. You go on a set, and you got the camera crew, sound crew, lighting, everyone in there, and if something’s not quite right with us, everyone’s got an opinion. “Oh, you can do this.” “You can do this.” All right? If the camera breaks down, I’m not allowed to say, “Can you try this?” If the sound have a problem, I’m not allowed to say, “Here, try this.” Or lighting and everything. It’s one of those. Or one of my pet hates is if someone walks on the set and goes, “I’ve got one of them at home. Why didn’t you ask?” Right? About a vase or something.

MJW: [laughing]

AWJ: And now I just turn around to them and say, “Well, I’ve got 5,500 other items dressing sets this week. Shall I run through every single one of them and see how many of them you got at home that you can bring to me?”

MJW: [laughing]

AWJ: Or the other one is they walk into it—and these are hardened crews now that’ve been around for years—walk into a location, and they’ll go, “Wow. This is perfect for this! How did you find this?” And you kind of go, “It wasn’t like this! We made it like this.”

MJW: [laughing] I see some before and after pictures that were taken during recces or whatever, and then as it ends up, and it’s just crazy.

AWJ: Well, that’s another thing I’ve been trying to do with Twitter, is showing what we do by showing the recce pictures and then the actual finished product, you know? And also, on Lady Chatterley’s Lover, for example, we built the Gamekeeper’s cottage in the woods. One of the most satisfying things about that was that the crew arrived and had to go up to it and touch it with their fingers, kind of realise that it wasn’t real. So that was nice.

MJW: Whoa.

AWJ: I heard that the current designer on Doctor Who said to my art director, “So where did you find that cottage?” And he went, “Oh, we built it.” He said, “No!”

MJW: [laughs]

AWJ: “Yeah, it’s actually built.” He said, “Well, I thought I knew those woods well!” And then he said, “So then you used one of the outbuildings at the manor house for the interior.” And he went, “No, no. We built that as well. That was in a….” “No, you didn’t!” “Yes, we did.” He went, “No, you didn’t,” and walked off. He couldn’t believe it.

MJW: [laughing] “You’re lying!”

AWJ: Yeah! You know, you can pull the wool over the eyes of another designer, I think that’s quite cool.

MJW: That’s amazing! So the orangery, which Steve always had fun things to say about with the lighting, you came in, and you basically redecorated the interior of it.

AWJ: Yeah. We were in there for six days, seven days.

MJW: Seven days.

AWJ: Right, and essentially, for a lot of that we were looking at Benedict. And Colm and I were stood there going, “We’re going to have to do something to give you some kind of life, something to go through something.” So that’s where we extend from, really, was to try and liven that space up and make it interesting, give interesting backgrounds, give interesting foregrounds.

MJW: So how were those foregrounds and backgrounds changed? because they were birds, right? On the wall?

AWJ: It was just essentially a magnolia wall when we walked in. So then we went to a golden yellow and painted these vines and birds and butterflies on. Then we put vinyls of the same thing on the windows to break up the windows as well because we were there for seven days. Again, for Steve to balance the light for seven days, we had to try and break the windows up a certain amount. Then I also built these totally pointless, weird things that we’ve got in the corners that had beveled, clear glass in them, so you could actually go behind them and shoot through them, so you would just play with them. But there was no earthly reason for them to be there, I think. It was just to break up the corners and have something to give reflections and play with.

MJW: Ah, that’s fascinating. So the wedding was beautifully done. Where did the ideas come from? Was it just that you’re working with the colouring that was already there? I mean, you had everything down to the name cards.

AWJ: Yeah, essentially we organised a wedding in, I think it was, three weeks.

MJW: Wow.

AWJ: And in the end, quite high spec. And also, to budget, which is what people often forget because apparently the average cost of a wedding in the UK now is about 40 grand.

MJW: Hoo!

AWJ: Right. We didn’t have anywhere near that.

MJW: Really?

AWJ: Christ, no.

MJW: [laughs] So I’m going to ask—and you will probably tell me no; you’re not going to tell me—but what’s the average budget for-?

AWJ: Can’t tell you.

MJW: Can’t tell me? Ok. So not anywhere near 40 grand. [laughs]

AWJ: No. Nowhere near. Not for a week’s filming for my department, no.

MJW: So you’ve gone through…at one point I had it memorised. Several different directors now.

AWJ: Paul [McGuigan], Euros [Lyn]-

MJW: Paul, Euros-

AWJ: Paul again.

MJW: Paul again, Toby [Haynes]…

AWJ: Yeah.

MJW: Then Jeremy [Lovering], and Colm [McCarthy], and Nick [Hurran], and Douglas [Mackinnon].

AWJ: Yes.

MJW: So what’s the difference in working with different directors?

AWJ: Well, they’re all different. There’s certain traits about a director that will always be there because they’re directors, right? Firstly, they lie.

MJW: [laughing]

AWJ: And some more. Yeah, right. No, I think a decent, a good director would have an element of selfishness about them in order to achieve what they have to achieve, what they have to try and get that kind of fixation on and get it, I think. Different directors are different. Like Paul’s an odd one in that he’s good both ways. He’s very technically good because he was a photographer.

MJW: I didn’t realise that.

AWJ: So technically he’s very good, and he likes to play with lenses and stuff and diopters, and doing things in-camera. But also the cast love him. He’s very good with the actors. But generally speaking, you tend to have either one or the other in that, you have someone who’s technically good and knows how to frame and what they want to do with the camera moves and stuff, and maybe not quite as good with actors and just let them do their thing and then just film them doing their thing. Or you have others who are good with the actors and develop things with them, and depend a lot on their DoPs to do the technical side.

MJW: Hm. So you sort of see this going on, but-

AWJ: Yeah, that’s the difficult thing. It’s part of the- You know, you never get the training- Well, I never got trained for anything, but two things you don’t get trained for is management with the amount of people that work for you, and the other one is the psychology of working with people and having to gain their trust and get them to like you.

MJW: How do you do it?

AWJ: Well, I don’t know.

MJW: [laughing]

AWJ: You know, because you can’t have any antagonism between you and a director otherwise it doesn’t work. You have to be there and help them tell the story.

MJW: So how much do you have to do with the actors? Do they have any input? I mean, obviously they’ve got to work with your props…

AWJ: If they’ve got input on things, then you talk to them, but I’m slightly different in that because of my wife Claire [Prichard], I generally get to know most actors via her anyway, not just from meeting them on set, you know? So I probably get a bit more insight into actors’ worlds than most designers do.

MJW: So what makes your job possible? What do you need to be successful? What do you have to have to be a better production designer?

AWJ: I have no idea. If you could bottle that, then you’d be all right. That’s the same in any world. I don’t think there’s a straight answer. Many people do it different ways. I know of, and I won’t name names, I know of people who have no friends. They don’t go to work to make friends. They go there, they shout, they bellow, they’re horrible to people, and they get an end result. And I’m not that kind of person. I believe that if you’ve got a happy crew, and everyone works together, then you end up with a better end product, I think. So that’s part of what I do is that I try and be as nice as- Well, not as nice as I can, but we try and have fun, for a start. If you’re having fun in work, then I think it kind of comes over, and then the trick is not having too much fun and making sure the work gets done. You just have what you do is good, and therefore, you have fun doing it.

MJW: So what’s the difference between working on something like Doctor Who and Sherlock?

AWJ: There’s no difference.

MJW: No difference?

AWJ: As far as I’m concerned, there’s no difference in the job. The job’s the same. All that’s different is the script, and therefore, the pile of problems that you solve.

MJW: I like the way that you talk about the script as being problems to solve. That’s really an interesting approach and not what I would’ve immediately thought of, but it makes a whole lot of sense.

AWJ: Yeah, because if you look at the whole thing, you’ll end up crying in a corner in a straightjacket. You have to break it down into its individual elements and how would you make that work, and then you talk through it all with producers, writers, directors, everyone, what they want and everything. And then you can influence that and say, “Well, why don’t you try it like this? Or do we do this?” And with locations as well, you can offer up something different to what they’ve originally written because if you can’t find something. And quite often, that’s one of the things I often say to location managers is, “Think outside the box as well. If you come across something dramatic or stunning, then offer it up. Let’s have a look.” It’s one of the things we…You know the Irene Adler scene [in “A Scandal in Belgravia”] when she appears, when John thinks that she’s dead, in the control room of Battersea Power Station, we weren’t doing that then. It was meant to be in an abandoned tube station. But we went and recced the power station because we were going to do the car bit there, right?

MJW: Yeah.

AWJ: And then they offered, “Do you wanna come see inside?” And we went in and we went, “This is amazing! We have to use this.” Right?

MJW: It was. It’s tremendous!

AWJ: So therefore, that scene ended up set in Battersea. So that was purely Paul and me on the recce going, “We have to use this. We have to use this.”

MJW: So what do you do on a recce? What’s your role?

AWJ: Well, it depends. There’s numerous recces. There’s an initial recce, which you go with a director and go, “Can we make it work?” And then that’s just normally it’s a looking and photographing the place. Sometimes it’s just photographing the place, going to look at it because you go with a location manager without the director, even. And you go back and then talk to them about it. Then you’ll go there and work out how you make it work. Then there’s a tech recce, before we start filming, with everyone. And that’s where I get grilled, because then, you’re there, and then every department goes, “Can we do this? Can we do this? Can we do this? Can we sort this? Can we do this?” And that’s when things change, or you have to think on your feet and deal with things, really.

MJW: So when do you realise that you need to build versus you’ve got a location for it?

AWJ: If it varies completely, sometimes it’ll be very, last minute because you have to solve a problem. Once again, if they can’t find something. Or sometimes you know immediately when the script arrives, you go, “Oh, that’s a build.”

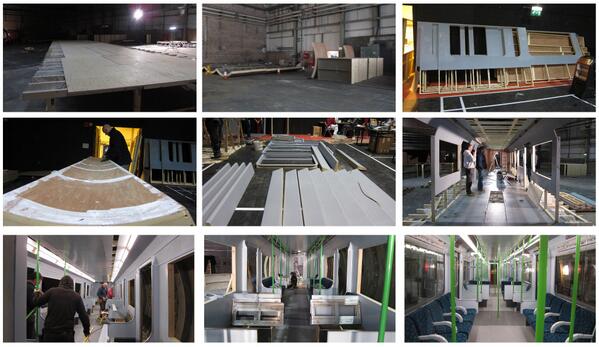

MJW: Like the tube car in “The Empty Hearse”?

AWJ: Yeah, we built that because it’s so expensive to film on the tube in London anyway. We needed to put a bomb on it, which they wouldn’t’ve been happy. We needed to lift the floor panels, which they wouldn’t’ve been happy with. You know, there was all those kind of elements. The amount of time we needed to be on there, and to be on a tube, you have to go on- The one station we did use, has 155 steps down to it because there’s no lift, because it’s an abandoned station. So just the physical accomplishment of getting the gear down ready for a day’s filming is immense. Getting everyone out for lunch and back down again, it’s all those things. And so you end up with maybe eight hours on camera? And so yeah, there’s numerous things, really. And balancing it, because it wasn’t a cheap build, but you balance it out for the two days on there. It worked out. It would be no more expensive, so we did it. It was much easier to do. It was all controlled; it was in the studio.

MJW: Well, it looked great. And it’s been interesting to see the behind the scenes pictures of the build. So you became pretty famous with the fans for tweeting the construction of 221b.

AWJ: Yeah, that was a bit of a surprise. It actually came about because an actor that was working with my wife at the time, or just before we started, had said that the problem with us was that we were too good at what we did, and no one could see it. If you’re good at what you do, then you don’t see it, right? Not that I’m agreeing with him, but I think his idea, what he’s saying, is true. Not necessarily about me. I had a Twitter account; I don’t do Facebook, don’t do any of that kind, but I had a Twitter account. I think I had a couple of hundred followers because a few people had worked out who I was, but that was it, and I hardly ever used it. And it was early days for Twitter as well; it wasn’t what it is now. And I just went, “I’ll just show what we do so that people can see what we actually do.” So I thought, and I just tweeted that picture of an empty space and said, “Right. Series three, here we go.” Right? And by the end of the week, I had 5,000 followers.

MJW: [laughing] It was just the empty space!

AWJ: Yeah. And every day then I tweeted a photograph, so essentially I was just doing like a photo blog, you know? A diary, really, of the set being built. And because I knew what had been seen- [producer] Sue [Vertue] was a bit nervous to start with, but then a lot of other people kind of jumped on the bandwagon, and we had to stop them, but she allowed me to carry on because I was sensitive to the subject matter, and I knew what had been seen before, what hadn’t, so there was no spoilers.

MJW: Right. We’d looked and looked and looked. We tried to find them. [laughing]

AWJ: Yeah, no I was very careful. I had to delete a couple very quickly when I spoiled a thing, but no. Yeah, so that’s why I didn’t do many on the special because obviously everything was new.

MJW: Everything.

AWJ: Right. Yeah, so I didn’t do any of the special [“The Abominable Bride”]. Hopefully, now I’ll be able to do a bit more again on series four.

MJW: Are you going to do the same thing and show us it being built up?

AWJ: Yeah. That’s the plan, yeah.

MJW: Awesome! Can’t wait. That’s going to be very exciting.

AWJ: Other than things that I might change.

MJW: [laughing] We’ll look for them! We will.

~END~

Arwel Wyn Jones: is an award-winning production designer and art director, known for Sherlock, Doctor Who and The Sarah Jane Adventures.

- Website: http://www.arwelwjones.com

- Twitter: @arwelwjones

- IMDB

Mary Jo Watts is the editor and founder of Powers of Expression, an on-line arts journal forthcoming in the Spring of 2016. She earned her Master of Arts in comparative literature from Rutgers University with specialties in modernist literature and film. MJ lives in Ithaca, NY where she fangirls over Sherlock under the name mid0nz.

a stupendously awesome interview–excellent questions! i can feel the enthusiasm from both of you–what a blast the actual Q&A must’ve been! thank you so much for sharing!

Hah! You seem as obsessed as me if it comes to the set!

Great interview with a great guy. Met him at Sherlocked last year.

Great interview. I’m a big fan of the show. I love the buzz behind the scenes too. Thanks for sharing.

Looking at this again as season 4 approaches, I am amazed at the technical expertise. Great Interview.

I’m revisiting “Sherlock” with my daughter now that shes old enough to appreciate it and tonight I was struck by the strange beauty of a shot and set in “The Great Game”. Watson goes to visit the room of a museum security guard who was murdered for discovering a secret to a Vermeer painting. There was just something about that scene that I felt like I remembered from somewhere, so I looked up the paintings of. Vermeer and it looks to me that the room is an homage to various works of his. . The color and the lighting are beautiful even though it is a messy apartment…there is even a convex mirror on the back wall. I’ve been looking up articles about it but really have found nothing. After reading your article here, I figured you might have an opinion on this. I really enjoyed your article and interview, by the way.